Hotter than a stolen tamale at a Texas hoedown

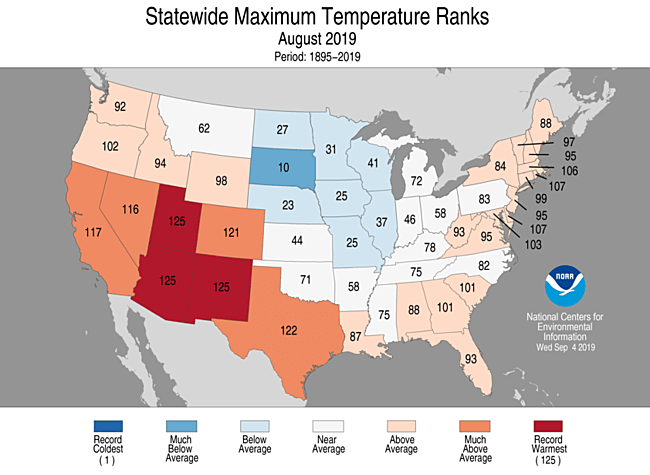

There’s another old saying, “Texas has four seasons. Drought, Flooding, Blizzard and Twister.” Which isn’t far from the truth. Texas is best described simply as the extreme ends of bad weather. So before we consider thinking about building a home using a shipping container I thought it might be a good idea to see how they do in the Texas heat. I had already bought the red 40′ high cube container for storage so I had something to run tests on. So shortly after we had our first day of 90+ degree temps with no clouds I decided to brave the heat at midday with an instant digital food thermometer and a pair of oven mits. Yes, the metal was that hot to the touch on the outside and I wasn’t going to take any chances. Next to states like Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico, NOAA reports Texas as “Much Above Average” during summer months like June thru August.

It had been a few months since I’d last gone in there so to say I was taken off guard by the initial heat blast is an understatement. I opened the doors and walked all the way to the far end of the container and within seconds my shirt was starting to soak through with sweat. The air was thick and a little painful to inhale, like opening a preheated oven. This was a LOT hotter than I had anticipated. Time to hurry up. I took the thermometer cover off and turned it on. Immediately it jumped to 90, 100, 110, 120. And this was just at eye level! I raised the thermometer above my head and saw it jump another 10 degrees. 132? Wow! I wonder what the roof feels like? This being a high-cube at 9′ 6″ tall I stood on a box and touched the end of the thermometer to the bare metal. It took less than two seconds and the readout jumped to 145 degrees Fahrenheit! My thoughts ran to something Robin Williams said with a thick southern accent on one of his HBO specials, “Is it hot enough for ya? Cuz I got sweat rollin’ down the crack of my ass like Niagara!”

Why was I thinking this? Because it was. Time to get out of here. Stepping back into the 90 degree heat was cold in comparison. At least there was a breeze. Again, wow. If there aren’t many insulation or cladding options then this mode of construction will be a No-Go even before it gets started. Time to look into how shipping containers can be insulated, what products are already out there, and how well containers conduct and store heat. I’m not just concerned with how hot they can get in summer but how cold they can become in the winter. No sticking my tongue to the side of this thing in Winter time. Even if I get a “Triple Dog Dare Ya”.

Everything on a shipping container is made of metal except for the treated plywood floors over the horizontally welded metal beams underneath. Maybe there’s a way to take advantage of that structure too in addition to taking advantage of this conducting effect in winter while minimizing it in the summer. Who knows, but first, time to do some research.

It didn’t take long for me to find the cheap, to really cheap, to really expensive insulation options already on the market. When using foam, internal insulation code requires the use of closed cell foam versus open cell. What’s the difference? Open cell foam is full of cells, “bubbles”, that are just that, open. Or to be specific, not closed or completely encapsulated. This tends to make the foam softer and more flexible but it also means the bubbles, which are just empty cavities, are exposed to the air. Which means they can absorb moisture. Closed cell foam is made up of compressed and completely encapsulated cells that are unable to absorb air or moisture. Although closed cell tends to be more rigid, they make a better candidate for internal insulation because moisture can’t collect as easily and produce things like mold. As you can imagine, closed cell is much denser than open cell with a density starting at 1.75 pounds per cubic foot compared to open cell which is usually around 0.5 pounds per cubic foot. And when there’s more density, there’s better insulation, or R-value. Open cell has an R-value of approximately 3.5 per inch and closed cell has around 6.0 per inch.

Which foam and application method to use

Both open and closed cell can be applied from a spray applicator tool but open cell expands to roughly 3 inches per application compared to closed, which is only about 1 inch. This means if you’re going with closed cell you’re going to have to do multiple layers to get the thickness you need. Add to the fact closed cell tends to be more expensive per application than open cell and you’re looking at a pretty hefty bill when using closed cell.

In the end though closed cell’s benefits far outweigh those of open cell. It’s more robust and can achieve 2x or more insulating rating for the same thickness and even comes in an E84 fire retardant rated version. As already mentioned, closed cell can act as a vapor barrier and is also resistant to water damage compared to open cell, so if your structure ever gets flooded you don’t usually have to replace closed cell foam insulation.

But wait, there’s more…sprayed insulation may allow for getting into all the nooks and crannies but there tends to be a lot more waste that has to be cut to make the whole thing flush and there’s a lot more mess due to all the over-spray that tends to occur in this form of application. And now the EPA is raising health concerns around the use of spray foam insulation. See https://www.buildinggreen.com/blog/epa-raises-health-concerns-spray-foam-insulation for a detailed article on this subject.

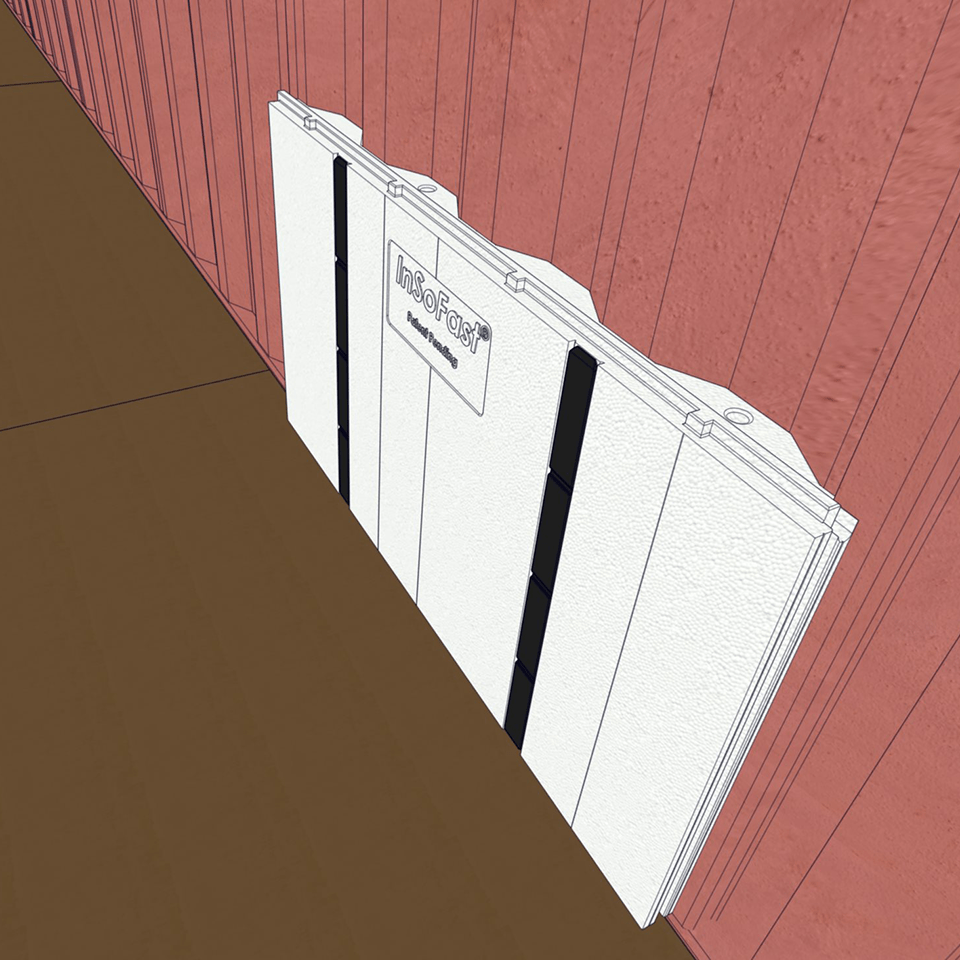

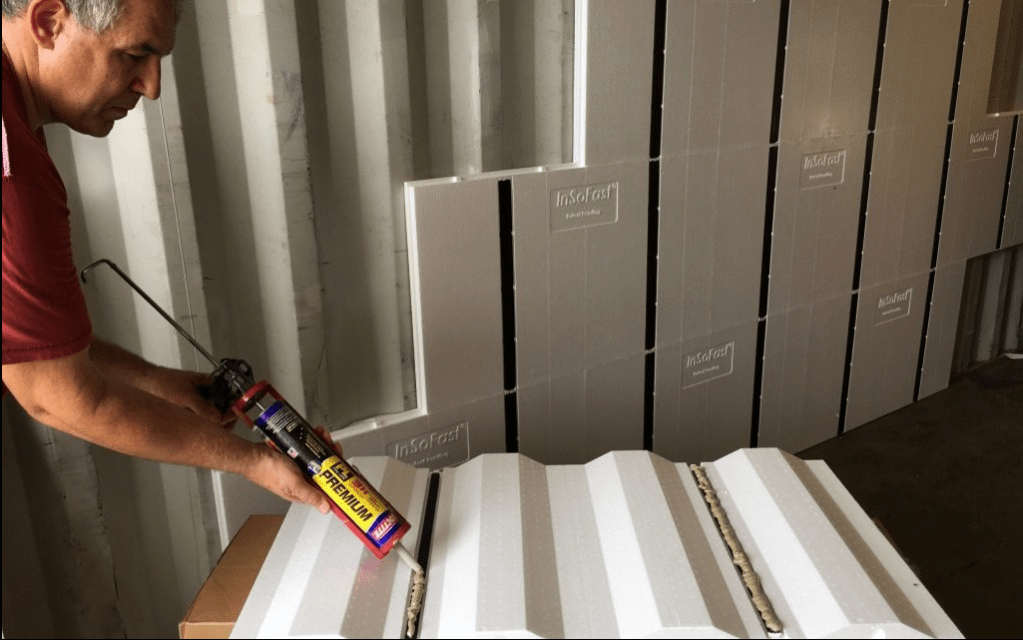

But because closed cell foam is extremely rigid, it can be made in preformed blocks for specific applications. Open cell does too, but again, tends to be more soft and flexible, and prone to breaking, compressing, or flaking at the edges. Enter one of the best solutions on the market. Insofast. Preformed, shipping container, closed cell foam panels. With built-in “studs” no less to mount whatever wall panels, dry-wall, or cladding you prefer. They make panels for the walls, ceilings, floors, and even the doors and include raceways for routing power and Pex tubing for water.

They’re not cheap, but they have a fantastic R-value, can be installed in a fraction of the time by one person, or two when you’re doing long runs or the ceilings, and they’re glued to the metal surface using Loctite so there’s no drilling through the metal walls. Insofast also produces panels for basements, concrete, and other applications. See insofast.com for more information.

More Questions

Now that I know what insulation I’m going to use, more questions popped up. How much R-Value or insulation do I need? Will one layer on the inside work or should I consider multiple layers? Or install it on the outside as well under whatever cladding I decide to go with? Do I need more on the roof or on the sides? Does the orientation of the shipping container matter? North-South or East-West? Will shading or different roofing materials, like elastic reflective paint or the possible (eventual) solar panels, make a difference? And again, is there any way to take advantage of this thing being made of solid CORTEN steel, especially in the winter? And how would I “switch” it on and off if there was?

Time to Science the $#!^ out of this! I’ve got to know How Hot Does it actually get, and where. Stay Tuned!

Credits

Page Photo by Nicolas Jehly on Unsplash